Renaissance Art

Honoring

Life and Death

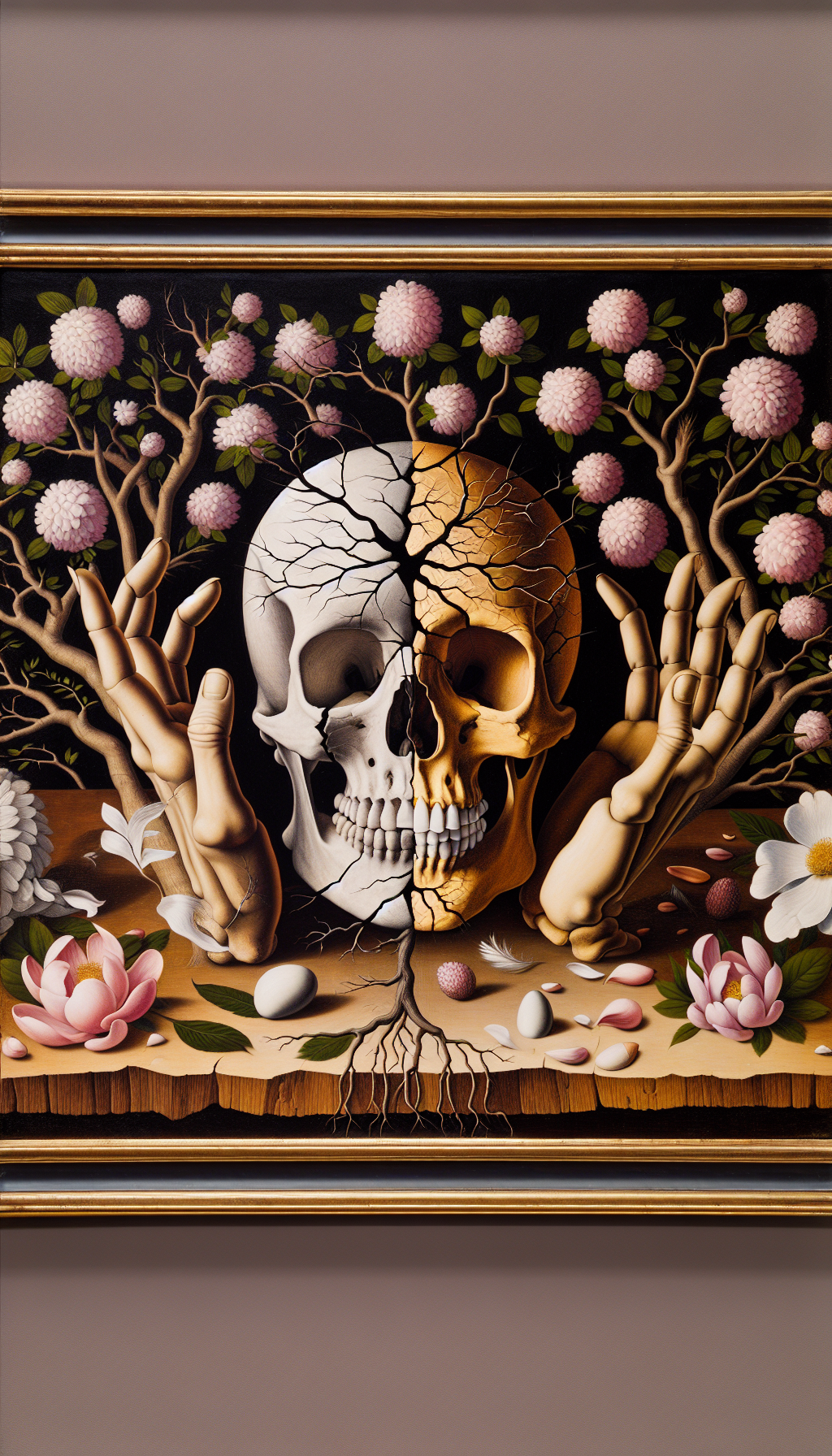

The Renaissance era marked a turning point in the artistic celebration of human dignity. Artists like Piero della Francesca immortalized individuals such as Federico da Montefeltro and Battista Sforza in diptych portraits, capturing Battista’s posthumous likeness with striking realism.

Her pallid complexion, rendered with meticulous care, transformed death into a subject of reverence rather than fear1. This practice echoed the Victorian tradition of post-mortem photography, where locks of hair and floral motifs accompanied images of deceased loved ones, blending mourning with commemoration1. John Everett Millais’ Ophelia further exemplified this theme, depicting Shakespeare’s tragic heroine in a serene yet haunting tableau. By foregrounding the dignity of Ophelia’s demise, Millais invited viewers to confront the fragility of life while affirming its enduring significance.

An image reflecting the Renaissance period, showcasing the concepts of life and death. The scene should prominently display mortality symbolized by a cracked skull and vibrant life represented through a lush, blossoming tree. The artistry typical to the Renaissance era, with its natural colors, balanced compositions and emotionality should be reflected. No people should be in the frame, rather the symbolic elements should carry the narrative.

Classical and Medieval Foundations

Ancient

civilizations laid the groundwork for art’s role in dignifying human

experience. Egyptian hieroglyphs and Minoan frescoes, though stylized, conveyed

symbolic narratives that elevated communal and spiritual values. Greek pottery

and Roman portraiture, meanwhile, celebrated civic virtue and individual

legacy, embedding human dignity within cultural artifacts. Medieval art,

dominated by Christian iconography, shifted focus to the divine image within

humanity. Byzantine mosaics and Gothic cathedrals framed human existence as a

reflection of sacred order, intertwining earthly life with eternal purpose.

These traditions established art as a medium for transcending mortality and

affirming the sanctity of the human form.

Reference:

https://www.fine-art-bender.com/european-art-history.html

Philosophical

Frameworks:

Dignity as Moral and Aesthetic Imperative

Kantian Autonomy and the Ethics of Art

Immanuel

Kant’s philosophy positioned human dignity in the capacity for moral autonomy,

asserting that rational beings must never be reduced to mere means. This

principle resonates in artistic creation, where the artist’s autonomy—their

freedom to envision and execute work—mirrors the moral self-legislation Kant

championed. For Kant, dignity was inseparable from the exercise of reason, a

concept challenged by modern debates such as France’s dwarf-throwing

controversy. Critics argued that using humans as entertainment props violated

their dignity, while performers defended their agency, highlighting the tension

between Kantian ideals and lived experience. Art, in this context, becomes a

battleground for dignity’s boundaries, demanding respect for both creator and

subject.

Reference:

https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1538409/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Social Justice and the Arts of Dignity

Initiatives

like Notre Dame’s Arts of Dignity exhibition exemplify art’s role in modern

justice movements. By showcasing student works on marginalization and

resilience, the program channels personal narratives into collective action.

Reference:

https://socialconcerns.nd.edu/arts-dignity

Similarly,

the 2015 Declaration on Beauty in Art and Human Dignity asserts art’s

capacity to “foster human beings to develop their full potential,” advocating

for art education as a tool for societal transformation.

Reference:

https://wya.net/wp-content/uploads/2015_WYA-Declaration-on-Beauty-in-Art-and-Human-Dignity.pdf

Such efforts align with philosopher Lewis Gordon’s view that art elevates

communities by fostering accountability and empathy.

- Vision -

Inspiration - Purpose - Target

- Goals - Strategy

2025?

Nothing is more powerful

than an idea whose time has come.

- Victor Hugo -

PicoPico della Mirandola and

the Renaissance of Human Potential

Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man redefined humanity

as a “chameleon-like” entity capable of ascending to divine heights or

descending to baseness.

Reference:

https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1538409/FULLTEXT01.pdf

This radical freedom, central to human dignity, found expression in Renaissance art’s exploration of individuality and emotion. Albrecht Dürer’s self-portraits, for instance, broke from medieval anonymity, asserting the artist’s unique identity as a vessel of divine creativity.

Reference:

https://www.fine-art-bender.com/european-art-history.html

Pico’s vision thus aligns with art’s power to reflect and shape human

potential, positioning the artist as both observer and architect of dignity.

The Baroque Era: Drama and Divine Humanity

Baroque

artists like Caravaggio and Artemisia Gentileschi infused their works with

visceral realism, dramatizing human struggle and resilience. Gentileschi’s

Judith Slaying Holofernes, for example, recast biblical heroism through a

feminist lens, asserting women’s dignity in a patriarchal society.

Reference:

https://www.fine-art-bender.com/european-art-history.html

The Baroque emphasis on chiaroscuro and emotional intensity mirrored the era’s

theological debates, framing human imperfection as a testament to divine grace.

Modernism and the Crisis of Dignity

The 20th

century’s upheavals prompted artists to interrogate dignity amidst

industrialization and war. Picasso’s Guernica transmuted the horror of civilian

bombings into a universal cry against dehumanization, while Mark Rothko’s

abstract canvases evoked the ineffable dimensions of human suffering.

Reference;

https://nathaniel.org.nz/single-mothers-are-saints/13-bioethical-issues/what-is-bioethics/414-art-dignity-and-the-human-spirit-synopsis-only

Rothko’s 1958 lecture at Pratt Institute underscored art’s preoccupation with

mortality, positing that great art must grapple with life’s transience to

affirm its sanctity. These works redefined dignity not as a static ideal but as

a dynamic resistance to annihilation.